The Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, Maryland has about one-thousand manuscripts and three-thousand five-hundred printed books in its collection. In order to better understand the connection between Medieval Europe and modern Baltimore, we wanted to know which part of that vast collection was composed of medieval manuscripts. Our investigation lead us to visit the museum after we had seen the manuscripts online, and also to solicit an interview with Lynley Herbert, the Assistant Curator of Rare Books and Manuscripts at The Walters Art Museum.

Close to ninety percent of the collection at the Walters Art Museum was assembled by the Baltimore collector Henry Walters during his lifetime. The collection was bequeathed to the people of Baltimore following his death in 1931, so we discovered that the collection actually belongs to the people of the city, not the Walters itself. The rest of the manuscripts were donated by other people or occasionally sought out and purchased by the museum staff after the death of its founders. The manuscripts contained in the Walters Art Museum allow not only local groups of Baltimoreans, but also scholars from across the globe to study the history of many different times and places such as Medieval Europe or sixteenth century Ethiopia by interacting with these relics from those time periods.

It was surprising to us that the collection is still growing today. We met with Lynley who during her time at the Walters has purchased two manuscripts: one a circa 1906 missal from German-occupied France, the other a 1603 Lutheran printed treatise later illuminated by a family that managed to get their hands on the piece. We asked Lynley about the process of buying the 1603 Lutheran treatise.

“Who buys the books? Does the Walters get grants through different places? How does it work?”

“We have some funds that we are allowed to use for acquisitions, but there is only a certain amount every year, so we have to spread it around between the different collection areas. I have to make a strong argument about why this is the thing out of everything out there right now that we should buy. I was interested in this book last year, but we were buying an important sculpture and it wasn’t feasible to buy a book at the same time. I checked the book this year, and not only was it was still available but they had dropped the price. The dealer was bringing it from Switzerland to a huge art fair that is held every year in New York, and a group of us were already planning to go to the fair, so we all went to see it together. I made my case for the book as we looked through it in the booth of the dealer, and ultimately everyone agreed it was an important addition to our collection. It was very intense, but exciting!”

Lynley is also in charge of deciding which books and manuscripts go on display. Due to their sensitive nature, manuscripts can only be on display for a limited time period. If a book is on display, it can only be on display for three months, and then it has to be closed and not opened again at that same spot for five years. This is because air quality and lighting conditions can harm the materials the book or manuscript is made from, and extended exposure to these elements can lead to fading.

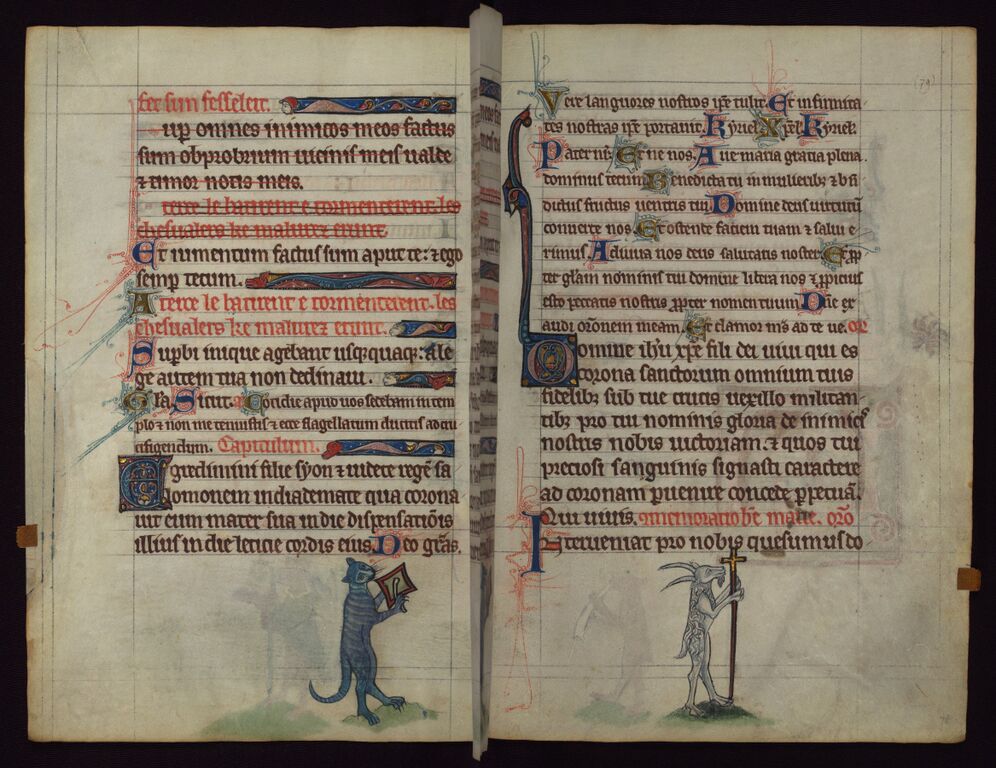

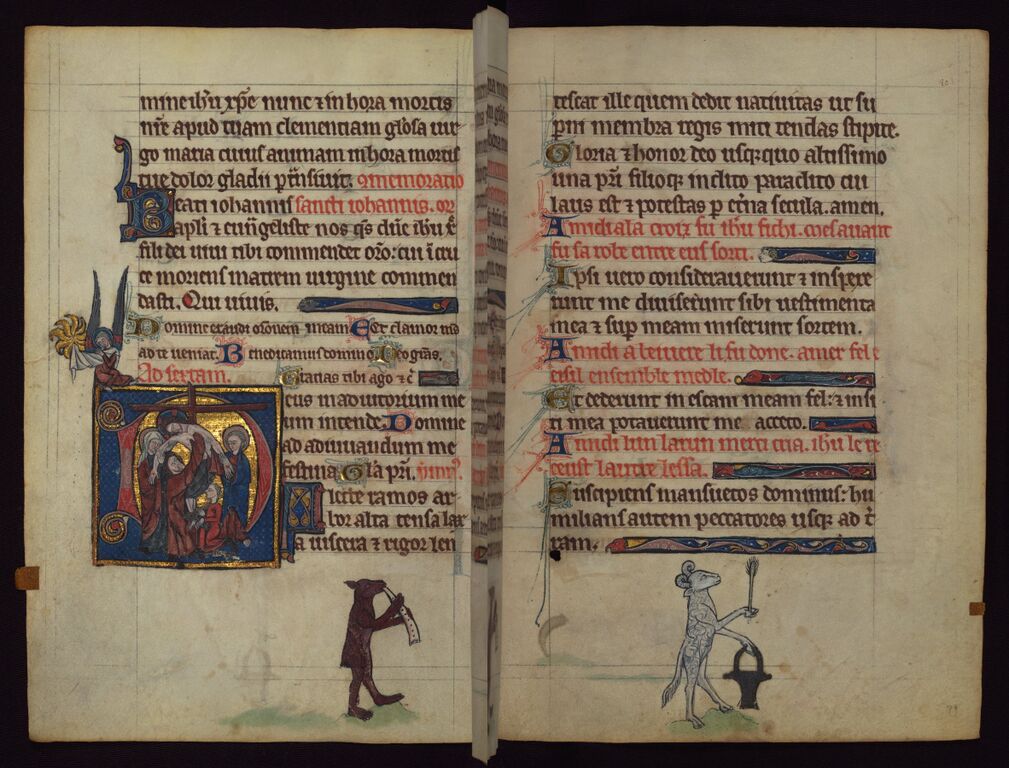

One of the most interesting pieces in the collection is an English Book of Hours that Lynley showed us in detail. We learned a lot about medieval manuscript books just by observing this example under her guidance. A book of hours is “a compendium of prayers and devotions” for individual use. Such books became the most popular devotional manuscripts of the later Middle Ages, that is, mostly after the 1300s. The name “Book of Hours” comes from their central and essential text, the Hours of the Virgin. “It is called “Hours” because it provides the texts to be recited and sung at each of the eight periods of the liturgical day.”11“Book of Hours” in Joseph R. Strayer and William C. Jordan (eds), Dictionary of the Middle Ages. Supplement I (New York: Scribner, 2003), 325. What’s particularly unusual about this book of hours, classified as “W.102” at the Walters catalogue, is the distinct illumination that it contains. Besides the very typical gold-leaf illumination in whole or partial sections of the folios, it includes many images of animals on the bottom sections of the pages. The images tell the story of Reynard the fox.

Lynley explained the story of the fox to us in the most clear way:

“Reynard the fox was a trickster, and there are all of these different medieval fables about Reynard, where he would get himself into trouble and get himself out of it again. In one of the stories he is playing chess with one of the animals, and he is caught cheating. The animal gets mad and nails him to the chess board – he bleeds and passes out, and they believe he’s dead. So the animals have a funeral procession, and that is what is depicted here [she is pointing to the bottom of the page]. There he is under the cloth, and the other animals are carrying him along. If you look carefully, though, you see that his eye is open and he’s not actually dead, but just looks like he is. So, then, if you keep going through the pages you get the wolf with the crosier (staff) which represents the bishop, and then a chicken with a censer that it’s swinging as if burning incense. These are all liturgical instruments, so you get this whole sense of a procession, a procession that keeps going across 17 pages. Then at the end, you arrive to the church. There, a rabbit is ringing the church bells. In the story, Reynard jumps up from the casket and reveals that he is not dead.”

[These are images of the pages from the English Book of Hours, showing Reynard being carried during his funeral procession and the other animals involved in the procession]

We could never have figured this out on our own. The jokes must have been especially funny for those who knew these stories well, as we know today the animals from the cartoons on the TV.

But Lynley also added a new layer to her interpretation:

“The actual text above this series of illustrations is about the death and resurrection of Christ. This is such medieval playfulness – it is kind of wrong, and funny at the same time! We aren’t sure how they would read this relationship, but there is a clear relationship between the text and the images. This is a remarkable thing, and I don’t know any other book that does anything quite like this. That is why this is my top manuscript, and one of the best in the collection.”

This English Book of Hours is, as Lynley explains, a most valuable tool to expand our understanding of medieval European Christianity.

After learning about the delicate nature of the manuscripts, we were curious about what the new technologies could do to keep them for future generations, for instance through the digitization of these relics from the past. The Walters Art Museum seems especially concerned because of its fantastic collection of manuscripts and its mission to make them available to all. The museum is in the process of digitizing its collection so that all of the works will be available for download and viewing on their website – for free! This means that anyone, anywhere in the world can not only see these manuscripts, but also download them for personal use and study. Considering the delicate nature of the manuscripts, the process of digitization must be incredibly complex. We asked Lynley how it was done.

“How does the whole digitization process work?”

“It’s complicated. We have a system for cataloging manuscripts specifically for digitization that has every kind of field that you could imagine, and which was designed for that purpose when we first started. We received an NEH grant about ten years ago, followed by 2 others, and we got a digitization cradle with the first grant. Not only do we have to put in the information about the manuscript, but also all of the little pieces that need to be digitized. For every side of every page of every book, you have to create a file in our system. But each item also has to go to conservation to make sure the book is in good enough shape to have the pages flipped. So generally, we make a list of the books we want to digitize, and request that those be conserved.”

Such a painstaking and detail-oriented process turns out to be a great occasion to research and know more about each item of the collection. Every time we take another look at a manuscript, we can discover more about it. It’s a never-ending process.

“What we’ve discovered is that not only the pictures, but even the text can be flaky. Sometimes the ink just doesn’t adhere well, depending on how they mixed the ink, or the way they finished the parchment. There are all kinds of issues, so what they’ve got to do [in the conservation department] is called “consolidation”. Basically, they’re taking the tiniest amount of glue with a microscope and they’re tacking down all the ink that’s still there to keep it from coming off. It took us much longer to digitize books with those issues than we had anticipated because their conservation took so much longer than we expected. After conservation and cataloging, we digitize.”

The operation of digitization appeared infinitely cautious and careful to us. She explained:

“We have a cradle that you sit the manuscript in, and you adjust the cradle for the size of the book so that it sits comfortably. There’s a little wedge that slides down, and you use very gentle suction to hold that page still, so that you can take a shot of the page. And then you release it, you raise the wedge and you flip the page, and you do the same with that page. It’s a very long, very complicated process. They photograph all of the pages going one direction through the book first, then they turn the book around and do all of the other sides of the pages. One book can take anywhere from a few days to a week, depending on its size. ”

One of the most interesting things about the digitization process, and one that raised our enthusiasm, is that the images of the manuscripts are free for anyone to use . There are no copyrights or rights that go along with the images. In this, the Walters has been taking the lead in sharing the precious resources with the general public, honoring the generous spirit of the museum founders in their gesture to give the collection to the city.

This has led to a lot of fascinating uses of the images the museum provides. Many of the images are now being used, for instance, in academic dissertations and book covers. Lynley informed us that she has had many inquiries, to which she always answers that the individual can do whatever they wish with the images. In fact, Lynley went to a conference in Kalamazoo, Michigan, where she found a booth set up selling mugs and t-shirts with images printed on them coming from several manuscripts from the Walters collection.

One concern of ours was that the digitization of the manuscripts and their availability online for free would have reduced the foot traffic to the Walters Art Museum. However, Lynley explained that making the images available has had almost the opposite effect, and that foot traffic has increased heavily by those interested in seeing the art and the manuscripts in person. Lynley described to us the different groups of people that come into the museum to take a close look at the manuscripts.

“I have lots of groups, everything from second graders from our summer camp who come to look at manuscripts as inspiration to make their own little books, to members of the local garden club who just want to see pretty paintings of flowers in books. I had a hundred bibliophiles from around the world come here to see our manuscripts this past fall, and I had to do six presentations of manuscripts in one day. So, I have to do lots of different things, and I have to kind of shift my brain depending on what I’m talking about and who I’m talking to, which is the biggest trick of the job. I also have scholars coming from around the world to see our manuscripts. I host about fifty scholars every year, and it’s usually about one to two full days of me working with them to help them with the books and their research.”

As we said before, every time we observe these beautiful books with care, there is more that they reveal to us about the past and the people who made them and used them throughout the centuries. Yes, it’s obvious that the digitized forms of the manuscripts can be found at manuscripts.thewalters.org. However, the digitized images are often not enough for many scholars who wish to study the manuscripts in person. In fact, Lynley often suggests to scholars that they study the content (that is, the texts) of the manuscripts online before coming in to study them materially, because they can spend more time on the details of the construction of the entire manuscript, study each page and section from up close, rather than figuring out what is being said in the text alone. By allowing hundreds of people a year to come into the museum and study the manuscripts, Lynley is giving back this treasure trove to not only the Baltimore community, but also the worldwide community of scholars who wish to study medieval history.

Figure 1

[1] “Book of Hours” in Joseph R. Strayer and William C. Jordan (eds), Dictionary of the Middle Ages. Supplement I (New York: Scribner, 2003), 325.

“Book of Hours” in Joseph R. Strayer and William C. Jordan (eds), Dictionary of the Middle Ages. Supplement I (New York: Scribner, 2003), 325. ↩

Medieval Baltimore

Medieval Baltimore