One of the most interesting artifacts from the Middle Ages kept at the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore is a twelfth century Spanish, Romanesque style “Chess Piece of a Queen”. While researching this piece I discovered that, in eleventh and twelfth century Spain, chess pieces could serve as luxury objects instead of being used as game pieces. “Chess Piece of a Queen” might be an example of such an object made for display. Sometimes chess pieces were carved of ivories considered too precious for game play. They became valuable gifts and objects for display among the nobility. Such pieces were also given to monasteries by nobles to ensure the favor of the church or protection. They could be sold for the monasteries’ maintenance. Other examples of medieval chess pieces are the twelfth century Lewis Chessmen in the British Museum and the Charlemagne Chessmen at the Cabinet des Médailles, Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris. In some cases, pious workmen created stained glass depicting chess pieces, or they used such depictions to embellish liturgical objects or fixtures11Donald M. Liddel et al, Chessmen (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Co.) 1937, 13..

“Chess Piece of a Queen” remains a unique piece that is still shrouded in mystery. What can be clearly determined is that the style is Romanesque and that it dates from the twelfth century. Romanesque art includes classical and Byzantine influences and a combination of stylized, abstract interpretations with realistic features.

The queen of the Walters Art Museum has almond-shaped eyes that peer left where her king would stand in game play, and a melancholy mouth demonstrative of the features represented by Spanish ivory carvers of the time22Hunt, John. “The Adoration of the Magi.” The Connoisseur : An Illustrated Magazine for Collectors 123 no. 537 (May 1954), 157.. In the miniaturized architectural setting provided for this figure, a sort of queen’s throne similar to a castle from which she emerges, the right angles and parallel lines are more Romanesque stylistic elements.

The queen is also carved in a style similar to the Islamic pieces of the ninth to tenth centuries that are kept in the Musée de Cluny in Paris. The tiered shape of the castle or throne with the rounded lower front is almost identical to a ninth or tenth century Arabic style chess king. The arches and circular relief carving that decorate the low, rounded front of the queen’s setting are identical to a remaining fragment of another king and horse of Arabic style, also from the ninth to tenth centuries33Hans and Siegfried Wichmann, Schach: Ursprung und Wandlung der Speilfigur in Zwolf Jahrhunderten ( Munich: Callwey, 1960), plates 6-10..

In both the Islamic pieces now kept in the Paris museum and the Spanish queen of the Walters Museum, the circular reliefs are used as border decorations as in the arches of the queen’s throne. This representation of the queen marks the artist’s attempt to impose a new realistic figure upon the traditional Islamic abstract form of the pieces kept at the Musée de Cluny . Simple cylindrical pieces were used instead of the ancient Hindu figures of animals which were part of the game as it originated in South Asia such as elephants and camels, or the figures of humans44Richard Eales, Chess: The History of the Game (New York: Facts on File Publications, 1985), 11.. The first introduction of the game to the West was made with Arabic style chess pieces that evolved this way and spread across frontiers, contributing to the adaptive nature of the game, and aiding its popularity. Those pieces were transformed, however, as the game spread through Christian Europe. They adopted the faces of new cultural landscapes, and forms that would be significant within the new European territories55James F. Magee, Jr., “Collection of Chessmen.” Bulletin of Pennsylvania Museum 11, no.43 (1913), 48.. Within a couple of generations after the year 1000 AD, chess pieces reflected the look of Latin Christendom.

Religion continued to have an impact on the transformation of the chess pieces, but local craftsmanship, familiarities, and styles also produced pieces unique to the geographic locations the game reached in medieval Europe. An example of this evolution is the addition of the queen to chess as a replacement for the Islamic vizier. The earliest documentation of this transition was a poem written by a German-speaking monk in the late 990s, “Versus de scachis”.66Marilyn Yalom, Birth of the Chess Queen (New York: Harper Collins, 2004), 15. The “Chess Piece of a Queen” from the Walters Art Museum is one example of a new piece created under local influence, as seen primarily in her headdress. The queen’s headdress in this piece is typical of the twelfth century royal garments and can be used as a definitive element that indicates its Spanish origin77Walters Art Museum Data File..

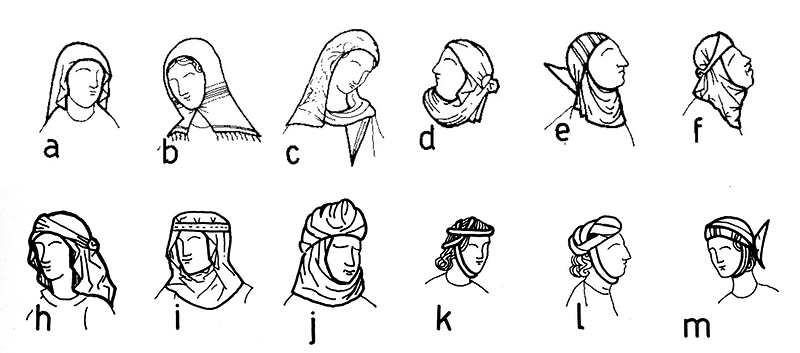

Types of female headdress depicted in Castilian miniatures from the thirteenth century, according to Gonzalo Menéndez Pidal88Gonzalo Menendez Pidal, La España del Siglo XIII leida en Imagenes (Madrid: Real Academia de la Historia, 1986), 88-89.

This aspect deserves further discussion. The headdress of the chess queen from the Walters collection could also be characterized as Byzantine because of the tighter fitting cap portion with draped sides that descend toward the body, covering the neck and shoulders. The Spanish queen’s headdress, however, shows the characteristic gathering of fabric under the chin which is also typical of an Iberian Islamic style headdress. This can be seen, for instance, on the figure of a Muslim woman playing chess with a Christian woman that is part of an illustration in Alfonso X’s Tratado de Ajedrez from the thirteenth century, as in the numerous examples shown here (most notably d, e, f or j), compiled from other Castilian manuscripts by Gonzalo Menéndez Pidal. The headdress, therefore, is an important element of the queen piece from the Walters Art Museum.

The piece at the Walters Art Museum can also be compared to one of the Romanesque chess queens of the twelfth century included in the collection known as “Lewis Chessmen” in the British Museum99James Robinson, The Lewis Chessmen (London: The British Museum Press, 2004), 18.. The Lewis queen now kept in London shares many similarities with the Spanish queen of the Walters Art Museum. Both are made of walrus ivory and both are seated. The headdress of the Lewis queen is a crown with descendant style drapery similar to that of the Spanish queen. A small relief border decorates the Lewis queen’s crown as well as the hem of her robe. As the Spanish queen directs her gaze towards her king, the Lewis queen acknowledges her king through subtle gestures. The same Lewis queen rests her head in her right hand, representing thoughtfulness, a reference to the previous Islamic vizier piece and to her role as the king’s advisor1010Robinson, The Lewis Chessmen, 17.. Another very similar queen piece holds a drinking horn in her left hand which may be for the benefit of her king1111Ibid..

Another Romanesque chess queen of the late eleventh century is in the “Charlemagne Chessmen” collection at the Cabinet des Médailles, Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris. This piece exhibits clear Byzantine influence by portraying a Prokypsis ceremony1212Michel Pastoureau, L’Échiquier de Charlemagne: Un jeu pour ne pas jouer (Paris: Adam Biro, 1990),16.. The Prokypsis involved a formal presentation of the emperor to the people and evoked a theophany through the use of symbolic material elements1313Slobodan Curcic, “Some Palatine Aspects of the Capella Palatina in Palermo”, Dumbarton Oaks Papers 31 (1987): 128.. The ceremony included an architectural box covered with curtains that would be drawn back by two royal attendants or courtiers, revealing the emperor of empress backlit by windows or candles to represent his or her divine qualities, the justification of their right to rule1414Curcic, “Some Palatine Aspects” , 128.. The attendants sometimes remained unseen to the audience to maintain the illusion of a supernatural effect. If they were holding candles, swords, or other imperial insignia, the objects would appear to float in midair, and the curtains would seem to have drawn themselves1515Dimiter Angelov, Imperial Ideology and Political Thought in Byzantium (New York: Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2007), 42..

Queen from the collection known as “Charlemagne chessmen”, from the Cabinet des Médailles Bibliothèque Nationale (Paris)

The Charlemagne carved chess queen stands inside a box, and her figure is revealed by two attendants holding back curtains. She stands on a raised platform, elevating her status above the audience. Windows are carved in this chess piece out of the back of the box to provide the backlight necessary for the staged ceremony to produce the mystical image of divine rule.

The walrus ivory used to produce the Spanish queen was for a long time the most mysterious aspect of the piece. Because of this material, the object was initially believed to be of German origin. File inconsistencies and inaccurate identification techniques from the 1920s to 1940s could be responsible for this, but it is difficult to identify exactly what accounts for this error1616Dr. Martina Bagnoli, Associate Curator of Medieval Art Walter’s Art Museum, telephone conversation, November 9, 2009.. Ivories in the Middle Ages were frequently reused and recycled, which makes tracing these materials very difficult1717Ibid.. Because of the convenient supply of elephant ivory from Africa and India, it was very common in the Mediterranean but also the most expensive. During the twelfth century, an unexplainable elephant ivory shortage plagued Europe1818James Robinson, The Lewis Chessmen (London: The British Museum Press, 2004), 57.. Norsemen then brought walrus ivory, primarily from Greenland, in uncarved, whole tusks to ports throughout Europe, including the Mediterranean. There were ivory workshops in Trondheim, Norway; Canterbury, England; and Cologne, Germany. Walrus ivory remained cheaper than elephant ivory, and the shortage of elephant ivory increased demand significantly. But other aspects of the medium also made it desirable, and it was by no means the least precious alternative to elephant ivory.

What was so special about this material? Arabs authors in the eighth century believed walrus ivory to have poison-fighting powers. Ivories were also believed in general terms to embody spiritual attributes of the animals from which they were procured1919Michel Pastoureau, L’Échiquier de Charlemagne: Un jeu pour ne pas jouer (Paris: Adam Biro, 1990), 24-26.. Christians related animals to moral aspects of life in an attempt to explain their purpose on earth. These explanations were written down and compiled into treatises called “bestiaries”. The walrus remained ambiguous in medieval bestiaries, most commonly associated with the whale. Medieval people believed the whale lured stray fish—metaphorical wayward Christians—into its jaws, but those who could resist its fragrant breath remained safe2020Michael J. Curley, Physiologus (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1976), 45.. The spiritual nature of the walrus ivory edified the owner’s nature solely through possession.

If we wish to understand the historical context of the chess piece of the Walters Art Museum, we must also look into other aspects of the history of the game of chess. The fact that this work of art is a chess piece in itself suggests the importance of the game in medieval Europe. Created in India between the sixth and seventh centuries, the chess game moved through Persia and the Middle East before making its first contact with medieval Europe through Spain, where it flourished between the eighth and eleventh centuries. Chess served functional purposes including contributions to mathematics, military strategy, and astronomy. It also developed into a minor art form, a symbol or social hierarchy, and an organized sport2121Richard Eales, Chess: The History of the Game (New York: Facts on File Publications, 1985), 11..

Chess never existed purely for entertainment and continued to develop into other uses as it spread through medieval Europe. Originally, chess presented itself as a game unfamiliar and exotic to Europeans2222Eales, Chess, 39.. These qualities fueled the popularity that helped chess become a staple in European society, primarily in Iberia, where the diverse cultural atmosphere allowed chess to proliferate and become a permanent fixture in society by the twelfth century. Spain was one of the places where chess was first introduced in the medieval European world. After the Islamic invasion of the Iberian Peninsula, from the early eighth century through the time of the Reconquista, the coexistence of diverse religious communities created a unique culture that incorporated Islamic and Christian elements as well as Jewish influences. The exchanges between this variety of peoples fostered unique cultural traits in Spain where the “Chess Piece of a Queen” most probably originated.

But was the adoption of chess always greeted with enthusiasm? Chess became extremely popular by the eleventh century among aristocrats, intellectuals, and even clergy which caused the Christian Church to levy opinions on the game. The Church initially opposed chess because the early versions incorporated the use of dice, associated with the evils of gambling. Clergy suffered the most severe restrictions, and ecclesiastical bans tried to limit the use of chess in Christian countries all over Europe. In 1061, a bishop in Florence was reprimanded for playing chess. The church authorities proclaimed:

Was it right, I say, and consistent with thy duty to sport away thy evenings amidst the vanity of chess, and to defile the hand which offers up the body of the Lord, the tongue that mediates between God and man, with the pollution of a sacrilegious game?2323James F. Magee, Jr., “Collection of Chessmen.” Bulletin of Pennsylvania Museum 11, no.43 (1913), 48.

Likewise, Bishop Guy of Paris in 1125 excommunicated priests who played chess. Casmir II, King of Poland who died in 1194 prohibited chess entirely. And Odon de Sully, Bishop of Paris who died in 1208, banned the game to the clergy under his authority.

The Christian church’s bans on chess did not stem directly from the game itself, but from the use of dice in association with chess. Dice incorporated an element of gambling and was therefore inherently evil. Pastoureau explains, “A dangerous activity, the use of dice was often related to episodes of physical assault, vendettas and manslaughter, all added reasons for church condemnation, and all thought to be clear proof of the diabolical nature of dice”2424Michel Pastoureau, L’Échiquier de Charlemagne, 21-22.. In spite of the prohibitions, dice were used by all levels of society2525Ibid.. In most areas of Europe, nevertheless, chess caught on as an aristocratic game not played by peasants who frequented dice games. The incorporation of dice tarnished the game’s social standing and was condemned by the clergy for the same reason. Despite the creation of the ecclesiastical bans and the logic behind them, these were never strictly enforced enough to stop the spread of chess and toward the end of the twelfth century, the bans were followed by a period of tolerance.

According to one specialist on the history of chess it was Gerbert of Aurillac, who became Pope Sylvester II, who may have strongly contributed for the initial spread of chess outside of Spain2626Richard Eales, Chess: The History of the Game (New York: Facts on File Publications, 1985), 42.. In the late tenth century, Gerbert traveled from Aurillac in France to the abbey of Santa Maria de Ripoll in Catalonia in order to study Arabic and Mozarabic translations of important texts on mathematics2727Betty Mayfield. Gerbert d’Aurillac and the March of Spain: A Convergence of Cultures. link to url, accessed December 2009.. He later taught in several monasteries outside Spain and as a consequence he may have started to incorporate the use of chess in his teachings. He may have adopted this practice from exposure to a sophisticated education nurtured in Arabic and Iberian sources2828Ibid..

The dynamic cultural atmosphere in twelfth century Iberia provided a fertile environment for the game of chess to take root as a common form of entertainment. Its adoption into all facets of medieval Spanish society from cultural transmission, military strategy, education, and regal entertainment made it a permanent element that continued to evolve throughout the medieval period. King Alfonso X’s Tratado de Ajedrez provides proof that chess reached preeminence in Castilian society later in the thirteenth century. His book promoted chess as a game that prevented idle minds for those who stayed indoors2929Pilar Garcia Morencos, Libro de Ajedrez, Dados y Tablas de Alfonso X El Sabio (Madrid: Patrimonio Nacional, 1977), 22. The book also located chess in the center of an entertaining philosophical debate on the prevalence of luck and the importance of logic3030Garcia Morencos, Libro de Ajedrez, 22.. The high intellectual regard with which Alfonso X held chess was related to another educational facet of the game. Alfonso’s use of chess in his court bridged social boundaries as well. He welcomed all chess enthusiasts to his court, regardless of gender, religion, or class. This diversity of people is demonstrated in the miniature illustrations in the book, depicting Muslim and Christian women as well as Alfonso himself playing against a woman of the middle class.

Indeed, Iberian women seem to have been involved with chess in different ways. For instance, valuable chess pieces were donated as women’s gifts to religious establishments. In 1008, Ermengol I, Count of Urgel in Catalonia bequeathed chess pieces to the monastery of St. Gilles in Provence, France, in his will3131Richard Eales, Chess: The History of the Game (New York: Facts on File Publications, 1985), 42.. Fifty years later, Ermengol’s sister-in-law, Countess Ermessenda, also bequeathed rock crystal pieces to the same institution. Her donation is an example of how aristocratic women in the Middle Ages would patronize and favor the church as appropriate to their high social status3232Marilyn Yalom, Birth of the Chess Queen (New York: Harper Collins: 2004), 45.. The “Ager Chessmen” were probably owned by the Catalonian nobleman Arnau Mir de Tost, a knight famous for his success in the eleventh century Reconquista south of Urgel. These objects are an example of what the chess pieces bequeathed by Countess Ermessenda would have looked like. The pieces were made of a rare material not meant for game play, but very valuable and owned exclusively by a wealthy individual. As Yalom notes, “most medieval chess pieces, those of greater size and more exquisite beauty, were not actually made to be used in the game itself. Their purpose was different, more serious and solemn: they were meant to be possessed, to be displayed and touched, to be simply kept in royal and church treasuries”3333Yalom, Birth of the Chess Queen, 22.. The “Ager Chessmen” are also an example of a set which does not include a queen, but still maintains a plain cylindrical Arab style vizier (as it was initially current in Iberia) even though the figure of the queen was known to chess both there and in other parts of Europe3434Ibid., 47..

By the twelfth century, chess paraphernalia including tabulas (chess boards) and pieces were already abundant in Spanish nobles’ wills and inventories3535Richard Eales, Chess: The History of the Game (New York: Facts on File Publications, 1985), 54.. Chess had spread from monasteries to the educational curriculum and was included in the formal education of noble youths3636Eales, Chess, 53.. Petrus Alfonsi, a Spanish Jew who converted to Christianity in 1106 and a well educated physician wrote Disciplina Clericalis under the patronage of Alfonso I of Aragon3737Marilyn Yalom, Birth of the Chess Queen (New York: Harper Collins: 2004), 52.. In a translation of Arabic tales into Latin, Petrus Alfonsi listed seven attributes of a knight: “The skills that one must be acquainted with are as follows: riding, swimming, archery, boxing, hawking, chess, and verse writing”3838Petrus Alfonsi, Disciplina Clericalis quoted in Birth of a Chess Queen, 52.. This source makes clear that the practice of chess in everyday education of nobles continued to spread becoming a permanent fixture within Spanish aristocratic society. Iberian Jewish authors such as Abraham ibn Ezra of Toledo (1092-1167), a respected rabbi and scholar, as well as Bonsenior ibn Yehia are also credited with poetry that provides first-hand evidence of the use of the chess queen piece in Spain in the twelfth century3939Yalom, Birth of a Chess Queen, 52.. The poems written by these men are other examples of chess’s presence in Iberian literary texts. Along with Petrus Alfonsi, Abraham ibn Ezra and Bonsenior ibn Yehia are representatives of the cross-cultural atmosphere in Spain that allowed the game to flourish.

In conclusion, the Walters Art Museum’s “Chess Piece of a Queen” is a prime example of the way the cultural landscape is reflected in the game, maintaining a balance of traditional style and newer representations used in the carving of chess pieces. Looking closely at this object and comparing it to other chess queens of the twelfth century reveal important differences that exemplify the unique traits of the piece, especially in the mystery of its ivory. The game’s importance and its continual intellectual evolution in Alfonso X’s court further reveal how it became a thriving, integral part of medieval Iberia’s dynamic culture beyond the functional and educational uses with which chess had entered Europe. As the history of Spanish art is further explored in coming years, perhaps the mystery of this chess piece will be fully revealed. In the meantime, this beautiful object remains a representative in the city of Baltimore of the vibrant nature of Iberia’s cultural exchanges during the twelfth century.

Donald M. Liddel et al, Chessmen (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Co.) 1937, 13. ↩

Hunt, John. “The Adoration of the Magi.” The Connoisseur : An Illustrated Magazine for Collectors 123 no. 537 (May 1954), 157. ↩

Hans and Siegfried Wichmann, Schach: Ursprung und Wandlung der Speilfigur in Zwolf Jahrhunderten ( Munich: Callwey, 1960), plates 6-10. ↩

Richard Eales, Chess: The History of the Game (New York: Facts on File Publications, 1985), 11. ↩

James F. Magee, Jr., “Collection of Chessmen.” Bulletin of Pennsylvania Museum 11, no.43 (1913), 48. ↩

Marilyn Yalom, Birth of the Chess Queen (New York: Harper Collins, 2004), 15. ↩

Walters Art Museum Data File. ↩

Gonzalo Menendez Pidal, La España del Siglo XIII leida en Imagenes (Madrid: Real Academia de la Historia, 1986), 88-89. ↩

James Robinson, The Lewis Chessmen (London: The British Museum Press, 2004), 18. ↩

Robinson, The Lewis Chessmen, 17. ↩

Ibid. ↩

Michel Pastoureau, L’Échiquier de Charlemagne: Un jeu pour ne pas jouer (Paris: Adam Biro, 1990),16. ↩

Slobodan Curcic, “Some Palatine Aspects of the Capella Palatina in Palermo”, Dumbarton Oaks Papers 31 (1987): 128. ↩

Curcic, “Some Palatine Aspects” , 128. ↩

Dimiter Angelov, Imperial Ideology and Political Thought in Byzantium (New York: Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2007), 42. ↩

Dr. Martina Bagnoli, Associate Curator of Medieval Art Walter’s Art Museum, telephone conversation, November 9, 2009. ↩

Ibid. ↩

James Robinson, The Lewis Chessmen (London: The British Museum Press, 2004), 57. ↩

Michel Pastoureau, L’Échiquier de Charlemagne: Un jeu pour ne pas jouer (Paris: Adam Biro, 1990), 24-26. ↩

Michael J. Curley, Physiologus (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1976), 45. ↩

Richard Eales, Chess: The History of the Game (New York: Facts on File Publications, 1985), 11. ↩

Eales, Chess, 39. ↩

James F. Magee, Jr., “Collection of Chessmen.” Bulletin of Pennsylvania Museum 11, no.43 (1913), 48. ↩

Michel Pastoureau, L’Échiquier de Charlemagne, 21-22. ↩

Ibid. ↩

Richard Eales, Chess: The History of the Game (New York: Facts on File Publications, 1985), 42. ↩

Betty Mayfield. Gerbert d’Aurillac and the March of Spain: A Convergence of Cultures. link to url, accessed December 2009. ↩

Ibid. ↩

Pilar Garcia Morencos, Libro de Ajedrez, Dados y Tablas de Alfonso X El Sabio (Madrid: Patrimonio Nacional, 1977), 22 ↩

Garcia Morencos, Libro de Ajedrez, 22. ↩

Richard Eales, Chess: The History of the Game (New York: Facts on File Publications, 1985), 42. ↩

Marilyn Yalom, Birth of the Chess Queen (New York: Harper Collins: 2004), 45. ↩

Yalom, Birth of the Chess Queen, 22. ↩

Ibid., 47. ↩

Richard Eales, Chess: The History of the Game (New York: Facts on File Publications, 1985), 54. ↩

Eales, Chess, 53. ↩

Marilyn Yalom, Birth of the Chess Queen (New York: Harper Collins: 2004), 52. ↩

Petrus Alfonsi, Disciplina Clericalis quoted in Birth of a Chess Queen, 52. ↩

Yalom, Birth of a Chess Queen, 52. ↩

Medieval Baltimore

Medieval Baltimore