Driving down Saint Paul street heading to Baltimore’s Inner Harbor you will find in your right a massive stone building with round arches in its main façade. It’s the Lovely Lane church, located at the corner of Saint Paul and 22nd streets. The most impressive feature of this church is its very large tower which can be seen from several city blocks away. Although most nineteenth-century Baltimore churches are styled in the Gothic fashion, Lovely Lane is one of the few examples in the city of a Romanesque building.

I was intrigued by the fact that this church resembles an old abbey near the towns of Ferrara and Ravenna in Italy: the abbey or monastery of Santa Maria of Pomposa. Many books mention that Pomposa was the original inspiration for the design of Lovely Lane.11James Dilts, John Dorsey, A Guide to Baltimore Architecture (Maryland: Tidewater Publishers, 1981), 201 So I set out to discover in what ways the two buildings differed, and what the similarities between them actually were.

The Lovely Lane church was completed in 1887, after almost four years of construction since the Methodists decided that they needed a new church in the city area located north of the then called Boundary Avenue (now North Avenue). This was a new area of growth for the city of Baltimore.22Mary Ellen Hayward, Frank R. Shivers, The Architecture of Baltimore. An Illustrated History (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004), 210-211

The new church was to be named initially the First Methodist Episcopal Church. Lovely Lane was the name of an original small forty-feet square church located downtown in the late eighteenth century, a modest building with “no stove nor backs for the benches that served as pews”33Asbury Smith, “A tour of Methodist Shrines in the Baltimore Conference”, American Methodist Bicentennial (Baltimore: The Baltimore Conference Methodist Historical Society, 1966), 58. In contrast, the property lot purchased a century later in Saint Paul Street was much larger to allow for not only the church itself but also the living quarters for the priest, and for the Sunday school. Another addition to this complex, but not a main topic discussed in this essay, was the original Goucher College adjacent to the church, also made of the same granite stone. Due to its location and size, the Saint Paul street church claimed the title of “the mother church of American Methodism” while also adopting, already in the twentieth century, the name of the old church from the late 1700s.

The church was designed by a young architect from New York who had worked as an assistant to Henry H. Richardson, the man whose huge influence helped establish the Romanesque style in America. His name was Stanford White, and he had traveled extensively in Europe, most notably in the North of Italy in 1879.44Paul Baker, Stanny: the Gilded Life of Stanford White (New York: Free Press, 1989), 56) White tried to reconcile his love of European building forms with the religious traditions of Methodism. By choosing examples of churches located in and around Ravenna in Italy, his own writing shows that he wanted to establish connections between the Methodists and the earliest Christian churches in Western Europe, influenced by Byzantium. In designing Lovely Lane, Stanford White wrote, he wanted to “reawaken the Greek spirit in architecture”. ((David Gilmore Wright, Calvin Corell, The Restoration of the Lovely Lane Church (Baltimore: Architectory, 1980), 47

The Abbey of Pomposa was built in the Middle Ages in the delta of the Po river, the major waterway of the big plain that makes the northernmost part of the Italian Peninsula. The monks settled their community in this marshy area where land and water merge into one single landscape. Their monastery was in fact located in an island set between the different branches of the Po delta, to this day known as the “Isola Pomposiana” (the word “isola” means “island” in Italian).55A beautiful printed map from 1781 shows the area, reproduced in Antonio Samaritani, Carla di Francesco, Pomposa. Storia, Arte, Archittetura (Ferrara: Corbo Editore, 1999), 265

Pomposa is first mentioned in texts dating from 878, and this community of monks reached its material and cultural peak in the eleventh and twelfth centuries when many manuscripts were copied in it, and songs kept flowing from the abbey. An inventory dating from the year 1093 listed a remarkable total of 68 manuscript books in the library of Pomposa. A very famous medieval musician, the monk Guido d’Arezzo (c. 990-1050), composed several of his works in Pomposa where he came up with more efficient ways to record the melodies that the monks chanted. The monk Peter Damian (c.1007-1072), famous for his letters sent to many influential people and fellow religious men, also visited this abbey and was a host there, as he dedicated one of his letters to the monks of the abbey66“Pomposa”, Enciclopedia Italiana (Roma: Enciclopedia Italiana, 1949), Volume 24, 844-845

The major reason for the location of the monastery of Pomposa in such a difficult area, which the monks had to drain and dry up in order to allow for the completion of their buildings, was their search for seclusion and isolation. The religious men wanted to develop their activities of prayer and their spiritual practice without interference. In their communal way of life, they followed the most common rule or model which prevailed mostly after Carolingian times: the rule of Saint Benedict.

The monks referred to their activities simply as “religion”, and historian Lester Little describes their goals this way: “the monks said prayers not just for themselves but for all, and not just for the living but also for the dying and the dead. They had the names of the deceased for whom they undertook an obligation to pray inscribed in registers called ‘books of life’ (libri vitae). (…) The persons named were to be remembered during the mass, but as there was no way all the names could be read out each time, the book was placed upon (plugged into, as it were) the altar. In this complex ancestor cult, the principal intermediaries, who had the task of saving the deceased, were the saints, whereas the intermediaries between the living and the saints were the monks. Any contact with the holy had to be made through them”.77Lester K. Little, “Monasticism and Western Society: from Marginality to the Establishment and back”, Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome 47 (2002), 89

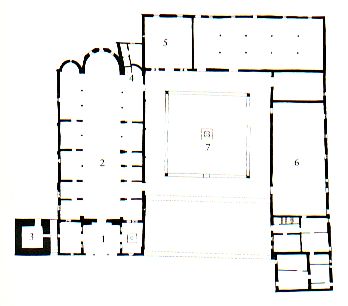

Praying was the main task of medieval monks. It comes as no surprise, therefore, that the central element of the Pomposa monastery was the church (marked 2 in the plan) and, within the church, the altar itself. The design of the church as a long rectangular space (called the “nave”) converging to the altar can be seen quite clearly in the plan. The entrance to the church was protected by a porch (1), and right adjacent to this porch was the imposing and very tall bell tower (3). The bell was used to call the monks to prayer. This tower, as I will explain later, was the most significant element the American architect took from the original medieval building of Pomposa.

All other spaces of the abbey were organized around a common open area, a central square courtyard named “cloister” (7). The monks spent their days together. They converged to the church to pray at regular times throughout the day, they ate together at the refectory (6), and they met to address common affairs in the so-called “chapter” room (5). All these different areas of the Pomposa abbey were specifically designed for the activities of the monks. In other words, the layout of the different parts that composed the monastery was entirely determined by the way the monks lived, and by their activities.

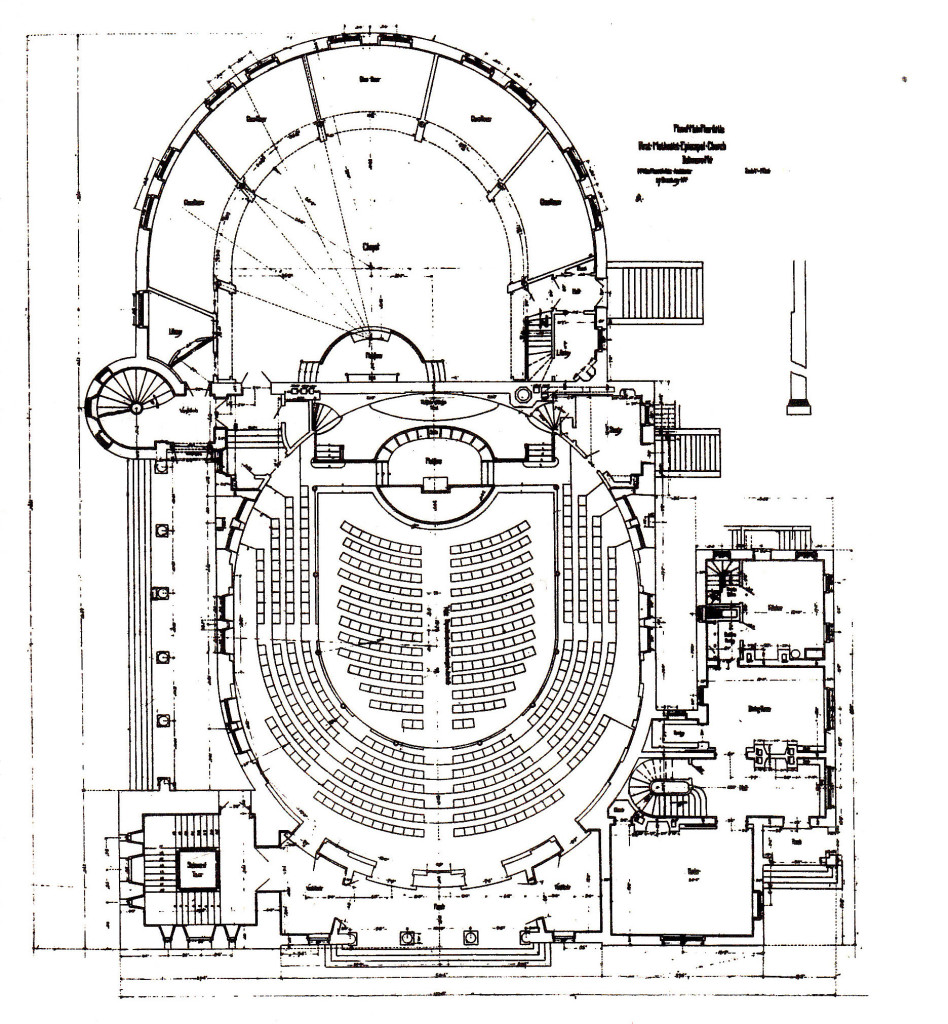

A simple visit to the Lovely Lane church in Baltimore will immediately reveal how different its spaces are from those of the medieval abbey. The most important area of the building is a large auditorium with an oval shape and symphony style seating. Behind it there is another large semi-circular area (named “the Chapel”) meant to be used for teaching Sunday school. There are numerous separate smaller rooms that lead to this second space centered on a beautiful small organ, just like the different rooms of the Benedictine monastery lead to the cloister.

The most important difference between Pomposa and Lovely Lane can be easily detected in their respective plans reproduced here. The layout of the central auditorium of Lovely Lane clearly shows how preaching, in the Reformed traditions of Calvinism and Methodism, takes precedence over other religious rituals. The main altar, in consequence of that, does not have a prominent position inside the space of the church – the pulpit does88Carl R. Lounsbury, “God is in the Details: The Transformation of Ecclesiastical Architecture in Early Nineteenth-Century America”, Perspectives in Vernacular Architecture 13 (2006), 2.

The pulpit here is not in a position raised high above the audience, however, nor is it enclosed in its own covered wooden structure. The visual connection between preacher and believers within the space of the church is the intended result of such choice. A guide to the building of churches published by the Methodists in 1875 in fact specified that “a good height for a pulpit” should be from 32 to 34 inches only. As historian Carl Lounsbury observes, “preaching was most effective when all eyes could be focused clearly upon this central platform”99Lounsbury, “God is in the details”, 15-16

Another interesting and related feature of the Lovely Lane main church space is the comfortable seating, in beautiful cast iron seats covered in velvet and disposed in ways similar to a theater in two levels (ground level and gallery). An innovative central heating system was also installed in the newly constructed building. All of this was meant to contribute to the comfort, ease, and dignity of the church activities. Those elements of the building, together with its warm dark red colors, were restored to their original form in the 1980s. That the idea of comfort and ease should be associated with church services in many ways determined the layout and internal organization of this building. That way, the building itself was meant to contribute to the purposes of the Methodist church.

In spite of the interior of the two buildings being so different, the architect Stanford White did take from Pomposa abbey the fundamental inspiration for the beautiful tower of Lovely Lane, together with the main façade and portico with columns and round arches facing Saint Paul street, replicated on the side of 22nd street.

The tower of Lovely Lane has a window distribution pattern that does not replicate exactly that of Pomposa’s tower. This is due not so much to the difference in the building materials – local granite stone in Baltimore, brick in the Italian monastery – as to the encounter between the architect’s reminiscent image of his model and the beliefs of his clients. White had wanted to put a cross at the roof of the tower but the building committee objected because the idea was “too Roman Catholic”. The resulting agreement allowed White to arrange the distribution of the windows in the tower in order to form a cross.1010Wright and Corell, The Restoration of Lovely Lane Church, 49

Overall, the Baltimore tower conveys an impression of strength due to its enlarged, broader base, and it becomes a massive upward element anchoring the double façade of Lovely Lane. The porch is not separate from the tower, as in Pomposa (compare the plans above), but it directly connects to the tower stairs, allowing access to it from inside the building. In contrast, Pomposa’s tower is almost like a detached element added to the rectangular church of the monks. It seems taller and more delicate, for it is full of intricate detail that cannot be found in the simplicity of Lovely Lane’s granite material.

In its similarities and differences from Pomposa, the Baltimore building nonetheless evokes the Benedictine abbey successfully bringing the beauty of its medieval forms into the modern American city.

James Dilts, John Dorsey, A Guide to Baltimore Architecture (Maryland: Tidewater Publishers, 1981), 201 ↩

Mary Ellen Hayward, Frank R. Shivers, The Architecture of Baltimore. An Illustrated History (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004), 210-211 ↩

Asbury Smith, “A tour of Methodist Shrines in the Baltimore Conference”, American Methodist Bicentennial (Baltimore: The Baltimore Conference Methodist Historical Society, 1966), 58 ↩

Paul Baker, Stanny: the Gilded Life of Stanford White (New York: Free Press, 1989), 56) White tried to reconcile his love of European building forms with the religious traditions of Methodism. By choosing examples of churches located in and around Ravenna in Italy, his own writing shows that he wanted to establish connections between the Methodists and the earliest Christian churches in Western Europe, influenced by Byzantium. In designing Lovely Lane, Stanford White wrote, he wanted to “reawaken the Greek spirit in architecture”. ((David Gilmore Wright, Calvin Corell, The Restoration of the Lovely Lane Church (Baltimore: Architectory, 1980), 47 ↩

A beautiful printed map from 1781 shows the area, reproduced in Antonio Samaritani, Carla di Francesco, Pomposa. Storia, Arte, Archittetura (Ferrara: Corbo Editore, 1999), 265 ↩

“Pomposa”, Enciclopedia Italiana (Roma: Enciclopedia Italiana, 1949), Volume 24, 844-845 ↩

Lester K. Little, “Monasticism and Western Society: from Marginality to the Establishment and back”, Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome 47 (2002), 89 ↩

Carl R. Lounsbury, “God is in the Details: The Transformation of Ecclesiastical Architecture in Early Nineteenth-Century America”, Perspectives in Vernacular Architecture 13 (2006), 2 ↩

Lounsbury, “God is in the details”, 15-16 ↩

Wright and Corell, The Restoration of Lovely Lane Church, 49 ↩

Medieval Baltimore

Medieval Baltimore